It was probably about the time that I got a trophy for getting my 300th headshot that I realized that Max Payne 3 has no idea what kind of game it wants to be.

On one hand, it wants to be a modern film noir masterpiece, an unflinching examination of a man trapped in a self-imposed purgatory of pills, alcohol and endless bloodshed, utterly unable to forgive himself for the past and move on with his life.

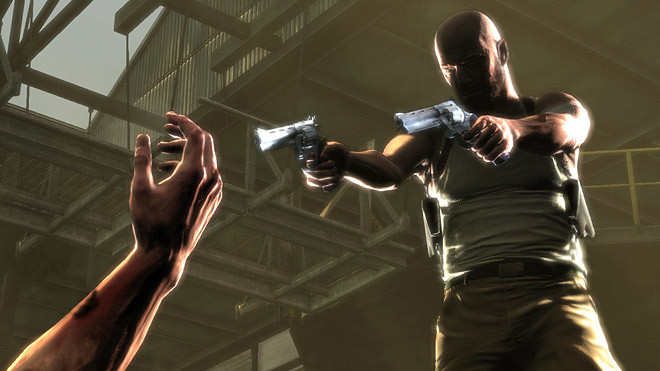

On the other hand, it wants you to dive through the air in slow motion and feel like a badass as you shoot ten thousand men right in the fucking face.

As it turns out, those don't mesh so well.

It's a common problem for a lot of games, where the gameplay is diametrically opposed to the themes of the story. Rockstar's games in particular have had this problem since they've all recently relied on the same character archetype: a man trying futilely to escape the sins of his past and start over. The "go anywhere, do anything" nature of Grand Theft Auto IV, for example, that allowed players to go on senseless rampages through the streets of Liberty City, also ran totally counter to protagonist Niko Bellic's claims of being reformed and wanting a peaceful life.

It's the same in Max Payne 3. Max wants nothing more than to leave his violent past behind and move on, a task he sets about accomplishing through the murder of literally thousands of people. As the game went on, I couldn't help but wonder: how many more people have to die so that Max can feel better about himself?

In the same vein, Max is supposed to be older and not as spry as he used to be, so the danger should be much greater. Max himself reinforces this idea several times, audibly musing that there's no chance he'll survive the next encounter. But Max Payne is a superhuman. He can dive through the air and down a flight of stairs and get up with nothing more than the grunt of a man whose knee aches on rainy days. He can get shot a half-dozen times in the chest and needs only pop a couple painkillers to be totally fine. He has such unbelievable reflexes that the world slows down around him, allowing him to shoot down incoming rockets with an Uzi while hanging from the side of a helicopter and also drunk.

In fact, the only earnest attempt made to make Max feel less capable than he was in his prime is that now he dies much more quickly. That would be fine if the game was designed around his age and limited what Max can do, but it's not. Instead, it equips him with a host of really cool abilities, like diving through the air, slowing down time, and dual-wielding weapons, but it never makes much sense to actually use them given how incredibly frail Max is. You're always going to be better off conservatively popping in and out of cover, completely ignoring his superhuman abilities, except for the occasional usage of bullet-time.

Just make sure you stay in cover when you use it, obviously.

The pretentious, post-modern, neo-chic, "video games are art, man" snob in me is tempted to call these design choices thematic and bold—that the player's constant urge to dive out of cover and play like the earlier games in the franchise represents Max's refusal to come to terms with his own limitations like a deluded old boxer convinced he can still take on the new blood—but in practice, it just felt like I was being punished for trying to have fun.

In fact, it's the multiplayer that ends up being the more interesting thematic component of the game. Max's bullet-time meter that allows him to bring the world around him to a grinding halt operates on the same logic as the single-player: fill the meter by getting kills. The crucial difference here, though, is that in multiplayer, since you don't have an endless stream of AI enemies to refill your meter, you really won't have bullet-time that often, so when you do, you feel like a god. You feel like you can dive through a second-story window and hurl bolts of lightning down upon all the ants fighting their petty war below. You feel like a young Max Payne again.

The single-player campaign never captures that feeling, too afraid that without a constant drip of adrenaline, players will lose interest. There's no discipline here, only the promise of another quick high.

And sure enough, since I always had plenty of bullet-time, I always took any opportunities I had to dive directly into the fray like an idiot. Yeah, I died a lot doing that. Like, a lot. And yet, diving directly into the fray like an idiot and dying was still way more fun than hiding behind cover and waiting for enemies to stick their heads out like every other modern third-person shooter. So yeah, whenever I had the option to flail through the air and shoot dudes in slow motion, of course I took it.

How many more people have to die so that Max can feel better about himself?

And shooting dudes is all you ever do in this game. You get dropped into a level and just murder, murder, murder until you suddenly find yourself at the end, covered in the blood of a thousand men.

This is by no means a problem unique to this game, but it stands out so much more here because this game actually aspires to be something greater than your average mindless video game. Instead, Max Payne 3 finds itself shackled by the limitations of the medium. In a story about how a man's all-consuming self-loathing over past violence is destroying him, your only means of interaction with the world is further violence.

It's a problem thematically—not to mention a concession that gameplay ultimately trumps story—but it's actually a problem for the gameplay side of things as well: there is zero variety in this game. Every level feels exactly the same, tasking you with getting from one end to the other and murdering anything that stands in your way. One level initially presents itself as a stealth level, which would've been a much-needed change of pace, but within seconds, it becomes apparent that you can't actually stealth your way through it and it's just bloody business as usual.

Another level starts in a typical bar in New Jersey, where Max kills a mobster's son, prompting his heartbroken, vengeful father to send dozens of guys after Max. The fight spills out into the otherwise peaceful surrounding neighborhood with zero police intervention, highlighting a) just how silly the sheer number of people you're killing really is, and b) how astoundingly unsympathetic Max is as a character.

"What the fuck is your problem, man?" a character asks Max near the end of the game, taking the words right out of my mouth. By this point, Max has left such an unfathomable blood trail behind him, with literally thousands of people dead in his wake, that that's really all you can say to the guy anymore. He's pathetic. He's insane. He's a monster. And he should've died years ago.

Even still, the thing that was on my mind the most while playing Max Payne 3 was that disgusting trophy, that virtual pat on the back for ending 300 lives with a bullet to the brain. I thought about how truly absurd and juvenile it is to reward a player for something like that. It's no wonder nobody outside of the industry takes video games seriously as a storytelling medium.

Whenever the general public gets incensed about a particularly violent or sexual game, the industry rushes to its defense, claiming that video games are a mature form of artistic expression fully deserving of the respect given to other mediums. Just look at another of Rockstar's games, Manhunt.

It put players in the shoes of a death row inmate tasked with earning his freedom by slaughtering gang members for a snuff film. There were three levels of executions the player could perform, with higher levels getting progressively more sadistic, but all levels would kill an enemy — you just chose how painful their death would be.

The game was deemed so graphic that it was actually banned in several countries. Defenders of the game claimed that the violence was thematic, meant to be a commentary on the increasingly violent nature of contemporary entertainment. If players feel uncomfortable performing these brutal executions, they argued, then the game has succeeded. The way "the Director" encourages you to be even more vicious with your kills is creepy because it's supposed to be. You don't need to kill an enemy in the most cruel and excruciating way possible, so why are you?

Max Payne 3 feels like

a dumb arcade shooter by comparison.

And that's what made Manhunt so fascinating. It didn't glorify violence at all; it made it so repulsive that players actually felt ill. It asked players to think about why they find violence entertaining at all, and where they draw the line. It had a message behind it.

Max Payne 3 feels like a dumb arcade shooter by comparison. It wants to prove that video games are capable of telling serious stories that can stand shoulder to shoulder with the film noir greats, but instead, it only serves to highlight the weaknesses of the medium.

It seems like you simply can't make an action game without the player murdering thousands of people over the course of the game, even if the protagonist is supposed to be a likable everyman or a guy who's trying to set his life straight. Max Payne 3 chooses to address that inherent hypocrisy the same way Uncharted 2 did, by merely pointing it out without actually solving anything. But what these games miss is that it doesn't matter how artsy or thought-provoking your cutscenes are anymore; what matters is if the game surrounding those cutscenes involves more than just diving down corridors in slow motion and shooting hundreds of dudes in the face. We need more games that try to push the medium forward.

And Max Payne 3 is not one of those games. Then again, it's not good at being the kind of dumb, mindless fun that the first two games in the franchise were, either. So I don't really get who this game is for, but it sure isn't me.

of dumb, mindless fun that the first two games in the franchise were, either. So I don't really get who this game is for, but it sure isn't me.

Max Payne 3 / $59.99 / PS3 [reviewed], 360, PC

Tweet

Tweet